THE CAMPAIGN OF 1976

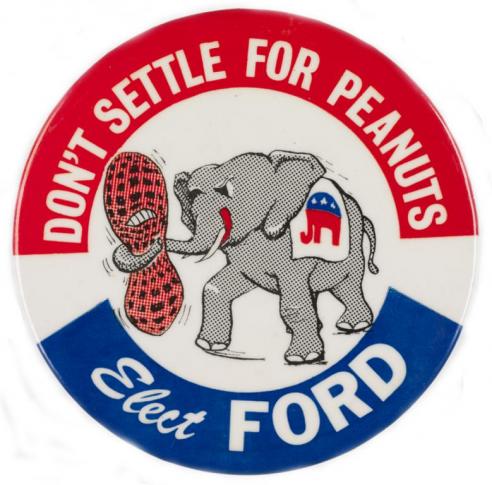

"If it weren't for the country looking for something in '76, Carter could never have gotten elected," pollster Patrick Caddell has observed. "He would never have been allowed out of the box. No one would have paid attention to him." Even today it is hard to imagine how a peanut farmer and one-term governor from Georgia with no national experience could become president. But by figuring out what Americans were looking for -- and giving it to them -- Carter did just that.

The country approached the 1976 election season already exhausted by a decade of war and scandal. The divisive Vietnam conflict and Richard Nixon's Watergate saga had undermined confidence in government and left public spirit at an all-time low. Traveling around the country long before other candidates began their campaigns, Carter listened, assessed the national mood, and decided it was the perfect time for an outsider like himself to run. While running essentially as a moderate to conservative Democrat, Carter emphasized his message of honesty, integrity, and character over specific issues. "I will not lie to you," he said, and he meant it. "The fact that he was unknown was part of his appeal," remembers Carter speechwriter Hendrik Hertzberg. "And he brought simple verities to the campaign trail: a promise not to lie to the American people, a promise to be good, a promise to love. And this was enough to bring him through the early primaries."

A year before the election, Jimmy Carter didn't even make it onto lists of potential presidents. But several years of quiet work paid off with a strong showing in the Iowa caucuses in January, putting Carter on the political map. Led by the "Peanut Brigade," a group of friends and volunteers from Georgia, Carter mounted a strong grassroots effort in New Hampshire, where a surprising victory made Carter the frontrunner. After a disappointing loss in Massachusetts, the next crucial battleground was Florida, where Democrats were counting on Carter to defeat George Wallace, the arch-segregationist former governor of Alabama. "By decisively defeating George Wallace," notes historian Dan T. Carter, "he not only succeeded in doing what the liberal [Democrats] wanted him to do, but transformed himself into a really powerful, major candidate."

Alarmed that this southerner they hardly knew might become their nominee, liberals mounted what became known as the "ABC Movement" -- Anyone But Carter. With the help of strong support from African American leaders like Martin Luther King Sr., Carter survived the challenge, and while he lost many of the remaining primaries, no single, strong candidate emerged to seriously challenge him. The only candidate to his right, Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson of Washington, had managed his campaign poorly and run out of money. And liberals, many of whom waited in vain for an ailing Hubert Humphrey to enter the race, ended up splitting their votes among a group of candidates including Senators Mo Udall, Frank Church, and Fred Harris, and late entrant Governor Jerry Brown of California. So by the time the Democrats descended on New York in mid-July for their convention, the nomination was Carter's.

On the Republican side, incumbent Gerald Ford faced a number of challenges. He had never been elected; he was not charismatic; and his controversial pardon of Richard Nixon tarred him with the brush of Watergate. Worst of all, he found himself in a tough battle with former California governor Ronald Reagan, the attractive, articulate spokesman for a new brand of western conservatism that had been gaining strength within the party since Barry Goldwater's run in 1964. Ford barely held off Reagan, and by the time he emerged from the Republican Convention in August, found himself behind by more than twenty points in most polls.

But as Carter's own pollster Caddell warned, Carter's support was "soft," and likely to melt under the glare of a long campaign. Ford exploited this weakness by accusing Carter of being "fuzzy" on the issues, fostering doubts among voters who liked Carter at first glance but didn't really know what he would do if elected. Carter's lead steadily shrank through August and September, with the help of a major mistake by the Carter camp. That summer, Carter had granted a series of interviews to journalist Robert Scheer for Playboy magazine, hoping to use its readership to show younger, more liberal voters that despite being a southerner and a Christian, he was not a prude. Toward the end of the interview, exasperated at not being understood, he said, "I've looked on a lot of women with lust. I've committed adultery in my heart many times." But when advance copies of the interview were released in mid-September, Carter found himself embroiled in a huge controversy, as voters struggled to reconcile Carter's squeaky-clean, Christian image with this frank talk. As journalist Kandy Stroud wrote, "The press was beginning to sniff failure."

By the time the candidates met for the second of three nationally televised debates on October 6, Carter's lead had nearly evaporated. But that night, in a debate over foreign policy, Ford blundered, telling an incredulous audience that "there is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, and there never will be under a Ford administration." "People couldn't see how a president would say that," remembers Carter's running mate, Walter Mondale, who helped Carter "pound away" at Ford for a week. "It stopped our slide. We started picking up a little bit, because people started having doubts about President Ford."

The election was so close that it was not until 3:30 am that Carter knew he had won. Carter received 50% of the popular vote to Ford's 48%, but his advantage in the electoral college was a thin 297 to 241, the smallest winning total since Woodrow Wilson's in 1916. At first glance, it looked like the Democrat had won with a traditional FDR/New Deal coalition: he carried the South, blacks, and labor (and each of these groups felt he owed them to some degree). But a closer look revealed some cracks in the foundation that would spell trouble for Carter. He was helped by an unusual number of crossover Republicans, and carried the South largely by attracting more white Protestants than a typical Democrat. These more conservative voters would be watching him carefully. He also scored weaker than most Democrats with northern Catholics and was eyed warily by liberals, who would be watching him carefully from the left of the political spectrum.

Nevertheless, Carter had pulled off one of the greatest upsets in American political history. "He offered a biography of what we wanted to hear," observes historian Douglas Brinkley. "It was the right message at the right time. And it didn't happen by accident. Carter created that message, knowing that that's what would win the day.

Source: "The Election of 1976." The American Experience. Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed May 24, 2016. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/carter-election1976/

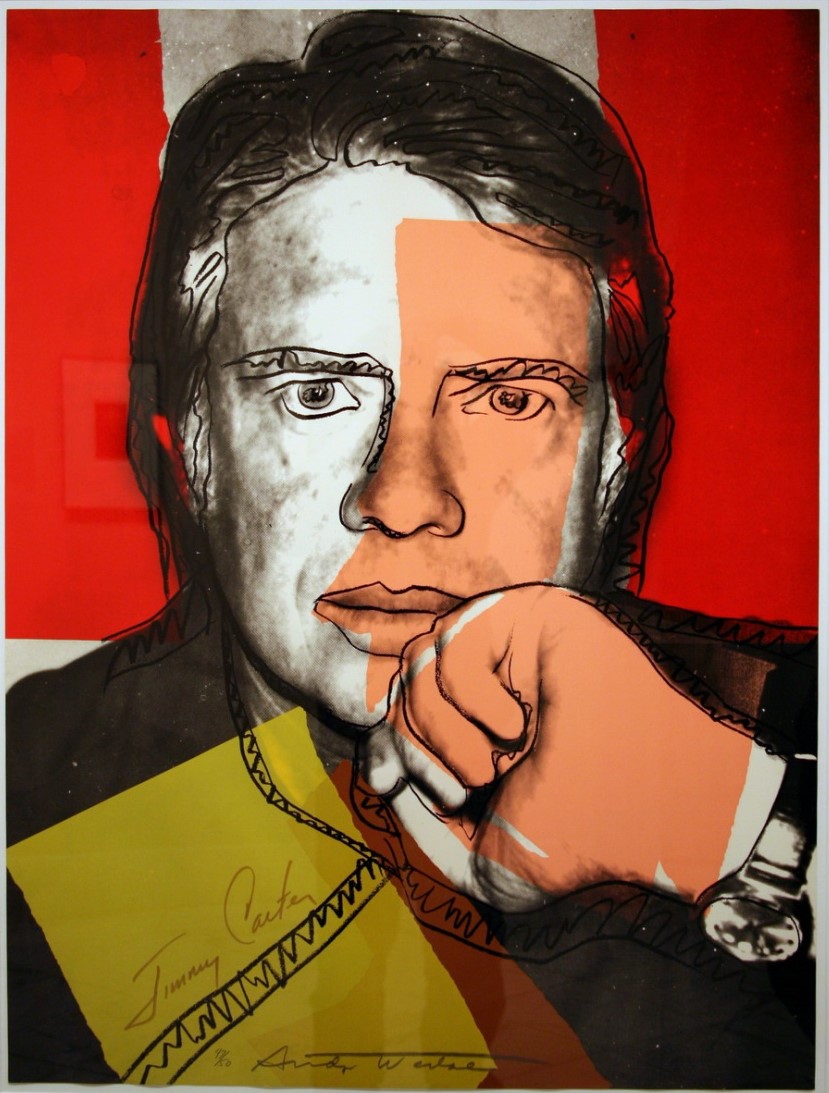

Andy Warhol. 1976. "James Earl Carter, Jr." Screenprint. The National Portrait Gallery, The Smithsonian Institution. Rights: The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

Anonymous. 1976. "Don't Settle for Peanuts: Elect Ford." Campaign button.