THE CAMPAIGN OF 1952

During an extraordinary military career, Dwight D. Eisenhower had done some things that few, if any, Americans had ever experienced. But he had not done something that was extremely common—he had never voted. Yet in 1948, many Americans hoped that the general would cast his first ballot—for himself as President. Even Harry S. Truman tried to interest Eisenhower in a run for the presidency. As the election year of 1948 approached, Truman, who became President when Franklin D. Roosevelt died in 1945, seemed to have little chance of winning a full term of his own. In a private meeting, Truman proposed that he and Eisenhower run together on the Democratic ticket, with Eisenhower as the presidential candidate and Truman in second position. Eisenhower rejected this astonishing offer and probably thought that he would never again have to consider the possibility of a run for the White House. He also spurned requests from prominent Republicans that he seek the GOP nomination for President.

Truman won an upset victory in 1948, but during the Korean War, he became extremely unpopular. Truman's decision to fire General Douglas MacArthur as commander of United Nations forces was an important cause for public disapproval of the President. So too was the deadlock in the fighting in Korea. Republicans expected to win the presidency in 1952, and Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio became the leading candidate for the GOP nomination. But some prominent Republicans considered Taft an isolationist since he had opposed the formation of NATO and talked instead about building up defenses in the Western Hemisphere. They tried to interest Eisenhower in the Republican nomination, confident that his popularity would carry him to victory and certain that his internationalist policies were essential to success in the Cold War.

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., of Massachusetts began an Eisenhower for President drive in the Republican Party. In public, Eisenhower said he had no interest in politics because he had to devote full attention to his duty as commander of NATO forces in Europe. But behind the scenes, Eisenhower began to offer encouragement to Lodge during the senator's visits to NATO headquarters near Paris. Finally, in January 1952, Eisenhower announced that he was a Republican and that he would be willing to accept the call of the American people to serve as President.

Soon there was clear evidence that voters preferred Eisenhower. In the New Hampshire primary, Eisenhower won a big victory over Taft. Yet in 1952, there was only a handful of presidential primaries. State conventions and party leaders chose most of the delegates to the nominating convention, and Taft had taken the lead before Eisenhower returned to the United States in June to campaign for the nomination. Some delegates—enough to make a difference in who got the nomination—were in dispute. At the Republican convention in Chicago, Eisenhower's political managers won a critical battle over the disputed delegates and managed to seat their delegates rather than Taft's in a few key states. As a result, Eisenhower won the nomination on the first ballot. For vice president, Eisenhower chose Senator Richard M. Nixon of California, who had helped his campaign managers secure votes in the dispute over delegates. Although he was just thirty-nine years old, Nixon had won national attention for his role in a congressional investigation of Alger Hiss, a former state department official accused of spying for the Soviets. Hiss went to prison after his conviction on a charge of perjury for denying that he had passed secrets to the Kremlin.

The Democrats picked Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, a witty and urbane politician whose thoughtful speeches appealed to liberals and moderate Democrats. His credentials were impressive: he was a Princeton-educated lawyer who had served as special assistant to the Secretary of the Navy during World War II, an influential member of the U.S. delegation to the United Nations after the war, and a successful governor with an enviable record of reform. But as a campaigner, he was no match for Eisenhower.

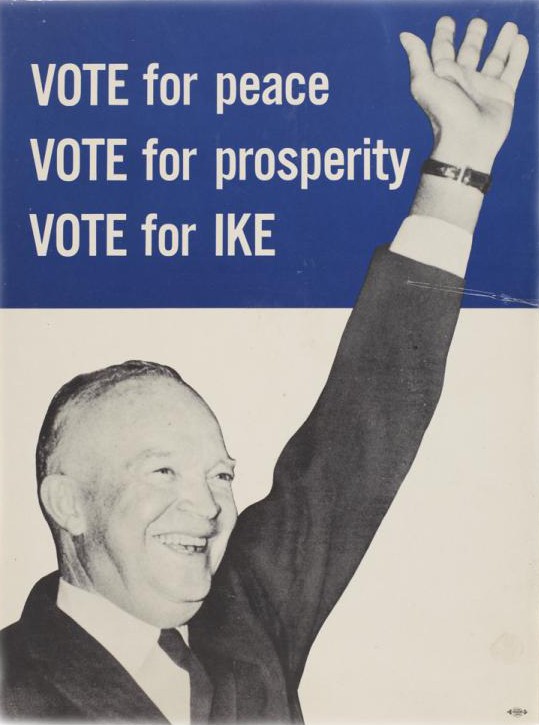

Eisenhower inspired confidence with his plain talk, reassuring smiles, and heroic image. He kept a demanding schedule, traveling to forty-five states and speaking to large crowds from the caboose of his campaign train. The slogan "I like Ike" quickly became part of the political language of America. Eisenhower also got his message to the American people through 30-second television advertisements, the first time TV commercials played a major role in a presidential election.

Yet it was not just Ike's personal charm that mattered, his campaign used a clever strategy of ignoring Stevenson—Eisenhower never mentioned his opponent by name—and attacking Truman. And Eisenhower had a formula for victory—K1C2 (Korea, Communism, and corruption). The stalemated war in Korea, corruption in the Truman administration, and Communist subversion were the issues that Republicans emphasized throughout the campaign. Eisenhower held a clear lead over Stevenson in the polls, as voters looked to Eisenhower to clean up what even Stevenson had called "the mess in Washington."

Eisenhower, though, had his own problems to resolve, as unexpected difficulties disrupted his campaign. The most serious was a scandal over whether Nixon had used campaign funds for personal expenses. This charge was particularly embarrassing because of Eisenhower's promise that his administration would be "clean as a hound's tooth." Nixon answered the allegations in a nationally televised speech on September 23. In a masterly performance, Nixon denied that he had done anything wrong, but vowed that he would not give up his daughters' little dog, Checkers, also a gift to the family, no matter what the consequences. The public responded to the "Checkers Speech" with an outpouring of support, and Eisenhower kept Nixon on the ticket.

Eisenhower provoked criticism for his own actions when he campaigned in Wisconsin and appeared on the same platform with Senator Joseph McCarthy. The junior senator from Wisconsin had been front-page news for more than two years with his sensational allegations that Communist spies had infiltrated the State Department as well as other parts of the federal government. McCarthy never provided evidence that led to a single conviction for espionage or treason, but he was a major power in the Republican Party. Eisenhower disliked McCarthy, and campaign aides told journalists that McCarthy would get his comeuppance when Eisenhower stood next to the senator at a campaign stop and praised General George C. Marshall, who McCarthy had denounced as part of a Communist conspiracy. But after campaign advisors urged him not to pick a fight with McCarthy in his home state, Eisenhower omitted his defense of Marshall, his former mentor and boss during World War II, when he gave his speech. Eisenhower endured a torrent of criticism, even from some Republicans, that he had compromised his principles for political advantage.

"I had never thought the man who is now the Republican candidate would stoop so low," President Truman declared about Eisenhower's failure to defend Marshall. Truman at first had stayed out of the campaign, but eventually he plunged in. He resented the Republican attacks on his record, and he thought that Stevenson's erudite speeches were going over the heads of the American people. Truman traveled the country in a whistle-stop campaign as he had in 1948 and made angry and extreme charges. "There was a time when I thought he would make a good President," Truman told a crowd in Ohio, as he discussed Eisenhower's qualifications. "That was my mistake." Eisenhower, Truman insisted, was a "stooge for Wall Street." On another occasion, he said that the general was the puppet of "Republican reactionaries" who were telling Eisenhower what to say. Republican "truth squads" followed President Truman and replied to what they said were his "fabrications."

The best Republican response came from Eisenhower as the campaign neared an end. "If elected, I shall go to Korea," Eisenhower declared, a pledge that stirred hopes that the general would find a way to end the fighting. Truman considered this promise a cheap campaign trick. The Truman-Eisenhower relationship, once good, died in the bitterness of the campaign.

On election day, Eisenhower won a big victory with 55 percent of the popular vote and a landslide in the electoral college, with 442 votes to Stevenson's 89. He even scored well in what had been the Democratic Solid South, taking a larger percentage of the popular vote than any previous Republican candidate and capturing Virginia, Florida, Tennessee, and Texas.

Eisenhower's coattails, however, did not carry many Republicans into Congress. The GOP won control of Congress, but only by narrow majorities—three seats in the House of Representatives, one seat in the Senate. In Massachusetts, Henry Cabot Lodge lost his Senate seat to John F. Kennedy. Indeed, while the election of 1952 was a triumph for Eisenhower, it was not a mandate for the Republican Party.

Source: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Dwight D. Eisenhower: Campaigns and Elections.” Accessed May 24, 2016. http://millercenter.org/president/biography/eisenhower-campaigns-and-elections.

Anonymous. 1952. "Meet Your Candidates! Vote Democratic * Tuesday - November 4, 1952." Democratic State Central Committee of Illinois. Brochure. From Adlai Today, the McLean County Museum of History. Accessed: May 24, 2016. http://www.adlaitoday.org/

Anonymous. 1952. "Vote for Peace, Vote for Prosperity, Vote for Ike." Poster. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540