THE CAMPAIGN OF 1948

Political and editorial cartoons have long been a part of the propaganda that influences the masses. Originating during the Protestant Reformation in Germany, this visual indoctrination gave support to the cause of Martin Luther's religious reforms. Because of the high illiteracy rate among the public at the time, these cartoons became known for their straightforward simple pictorial nature. American political cartooning assumed this direct appeal to the masses as well. Tracing its origins to Benjamin Franklin and his cartoons asking for unity during the American Revolution were the first of their kind in the new country.

Political cartoons in the United States came in and out of prominence through the early nineteenth century. Not until the late 1880's did this media gain true merit again. Pressing for social and political change, the artist Thomas Nast began creating charicatures of the Tweed Ring at Tammany Hall in New York. His approach of using lively pictures that appeal to the masses and using very few words was very effective in enlightening his multi-ethnic New York readers to the injustices of city government.

The Truman administration was no stranger to the sneers and jeers of political cartoonists. Facing such controversial issues as the desegregation of the armed forces, dropping of the atomic bomb, the cold war, the fair deal, the Republican takeover of Congress, and the 1948 presidential campaign, political and editorial cartoons were commonplace. President Truman, no matter how scathing, always professed a fondness for the cartoons and became an avid collector of them in his post-presidential years.

The 1948 presidential campaign of Harry Truman has been dubbed one of the greatest political campaigns of the modern era. No one, Republican or Democrat gave incumbent President Truman any hope of defeating a Republican nominee....especially Thomas E. Dewey, governor of New York. Southern Democrats (Dixiecrats), led by Senator Strom Thurmond, and Progressives, led by Henry Wallace, had splintered from the Democratic Party leaving a fractured and hopeless group searching for a saving grace in the '48 election. A stronger civil rights platform in the Democratic party was the cause of this rift. Beginning with his 1948 State of the Union address, Truman quickly found that his ten month campaign would be long and hard. Truman and his entourage embarked upon a whistlestop campaign of immense proportions travelling more than 21,000 miles, stopping in more than 250 cities, and delivering more than 300 speeches. Even with the nomination of his party behind him, none but Truman believed that the presidency could be won. Magazines, newspapers, and pollsters had written him off. Sidney Shallett in the Saturday Evening Post wrote, "The Governor of New York talks not like a man who wants to be President, but like a man who already is President in everything but name, and who merely is awaiting the inaugural date before taking over." This optimism ran high late into the political season. As November approached, no relief was given to the Truman campaign. Truman wrote to his sister in the autumn of 1948, "It will be the greatest campaign any President ever made. Win, lose, or draw people will know where I stand..." Even the Democratic party had lost faith and refused to spend their usual exorbitant amounts of money on the election. As election day drew near, the whistlestop campaign drew to a close and President Truman returned to Independence to await election day.

Harry Truman described the day best at dinner of the Presidential Electors on January 19, 1949:

...I had my sandwich and glass of buttermilk, and went to bed at six-thirty. And along about 12 o'clock, I happened to wake up for some reason or other, and the radio was turned on to the National Broadcasting Company. And Mr. Kaltenborn and Mr. Harkness were reporting the situation as it then developed. Mr. Kaltenborn was saying, "While the President is a million votes ahead of the popular vote, when the country vote comes in Mr. Truman will be defeated by an overwhelming majority." Mr. Harkness came on, and analyzed the situation as it was then, and as Mr. Kaltenborn had recorded it. And to the sorrow of myself, and to those who were listening with me, it looked very much as if the elction would be thrown into the House of Representatives because, of course, it was not possible for me to get a majority of the eletoral votes. I went back to bed, and went to sleep. About 4 o'clock in the morning, the Chief of the Secret Service came in and said, "Mr. President, I think you had better get up and listen to the broadcast. We have been listening all night." And I said, "All right." I turned the darn thing on, and there was Mr. Kaltenborn again. Mr. Kaltenborn was saying, "While the President has a lead of two million votes, it is certainly necessary that this election shall go into the House of Representatives. He hasn't an opportunity of being elected by a majority of the electoral votes of the Nation!" And Mr. Harkness came on and analyzed the situation. I called the Secret Service men in, and I said, "We'd better go back to Kansas City, it looks as if I'm elected!" Along about 10 o'clock, I had a telegram which said that the election was over, and that I should be congratulated on the fact that I had won the election. Apparently it was too bad, but it happened!

President Truman managed to carry 24,105,812 popular votes to Dewey's 21,970,065. Carrying 28 states and 303 electoral votes, Truman easily defeated Dewey, who had only 189 electoral votes from 16 states. Truman suprised the pollsters and the nation by returning to the White House.

Source: "Introduction." Student Activity: Presidential Campaign of 1948. The Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Accessed: May 24, 2016. https://www.trumanlibrary.org/teacher/campaign.htm

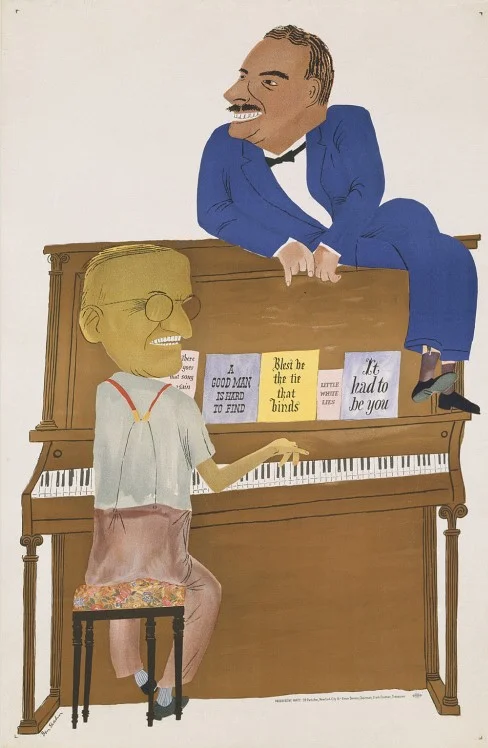

Ben Shahn. 1948. "The Duet: Truman and Dewey." Amalgamated Lithographers of America. Color Lithographic poster. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Accessed: May 24, 2016. http://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.72.69

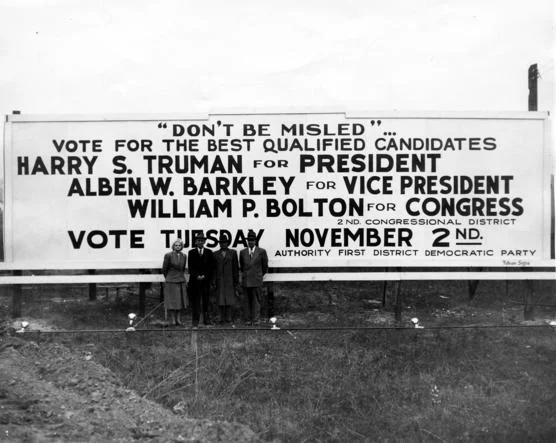

Anonymous. 1948. "1948 Campaign Sign in support of President Truman." Black and White Photograph. The Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Accessed: May 24, 2016. http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=20612

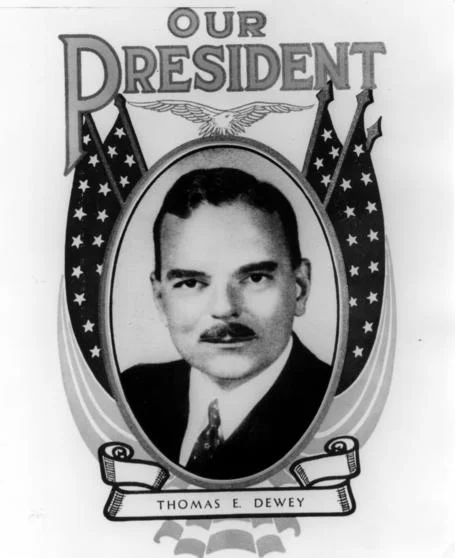

Anonymous. 1948. "Campaign poster of Thomas E. Dewey." Campaign Poster. The Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Accessed May 24, 2016. https://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=17869

Anonymous. 1948. "Get in the Fight for States’ Rights." From The Smithsonian Institute “Oh Freedom: Teaching African American Civil Rights Through American Art at the Smithsonian”

Smithsonian American Art Museum & Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture. http://civilrights.si.edu/items/show/43