THE CAMPAIGN OF 1908

After his 1904 electoral victory, Theodore Roosevelt promised publicly not to seek the presidency again in 1908. While he later regretted that decision, he felt bound by it and vigorously promoted William Howard Taft as his successor. Both Nellie Taft and Roosevelt had to persuade Taft to make the race. Even with the presidency in his reach, Taft much preferred the U.S. Supreme Court chief justice appointment.

It was generally expected that Taft would be Roosevelt's man in the White House, and Taft himself vowed to continue Roosevelt's progressive policies. Still, up to the last minute before Taft's nomination at the Republican Party convention in Chicago, Nellie Taft feared that Roosevelt might announce his bid for a second elected term. It almost happened on the second day of the convention, when a spontaneous and wild demonstration produced a forty-nine minute stampede for Roosevelt—the longest-lasting demonstration that had ever occurred at a national political convention. Only when Roosevelt sent word via Senator Henry Cabot Lodge that he was not available did the convention nominate Taft on the first ballot. The final count gave Taft 702 votes (491 votes were needed to win) in a field of seven nominees. The Democrats once again nominated William Jennings Bryan, the twice-defeated candidate who still personified the populist politics of the Democratic Party and the moral fervor of its "silverite" wing.

At Nellie's urging, Taft announced that he intended to drop thirty pounds off his 300 pound plus weight for the campaign fight ahead. He retreated to the golf course at a resort in Hot Springs, Virginia, where he stayed for much of the next three months. His campaign, once it started, depended heavily upon Roosevelt for speechmaking, advice, and energy. Journalists bombarded the public with jokes about Taft being a substitute for Roosevelt. One columnist explained that T.A.F.T. stood for "Take Advice From Theodore." Nothing could hide Taft's dislike for campaigning and politics. His handlers tried to turn his sluggish style into a positive asset by describing Taft as a new kind of politician—one who refuses to say anything negative about his opponent. For most voters it was enough, however, that Taft had pledged to carry on Roosevelt's policies. His victory was overwhelming. He carried all but three states outside the Democratic Solid South and won 321 electoral votes to Bryan's 162. In the final tally for the popular vote, Taft won 7,675,320 (51.6 percent) to Bryan's 6,412,294 (43.1 percent). Socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs won just 2.8 percent of the popular vote, or 420,793.

Source: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “William Taft: Campaigns and Elections.” Accessed May 23, 2016. http://millercenter.org/president/biography/taft-campaigns-and-elections.

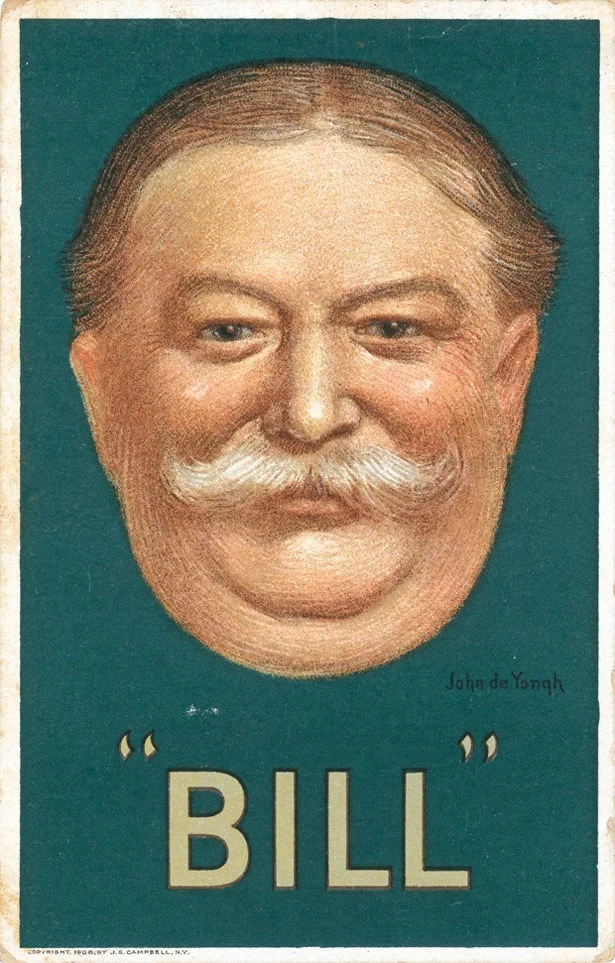

John de Yongh. "Bill." J.S. Campbell. Lithographic Postcard. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540

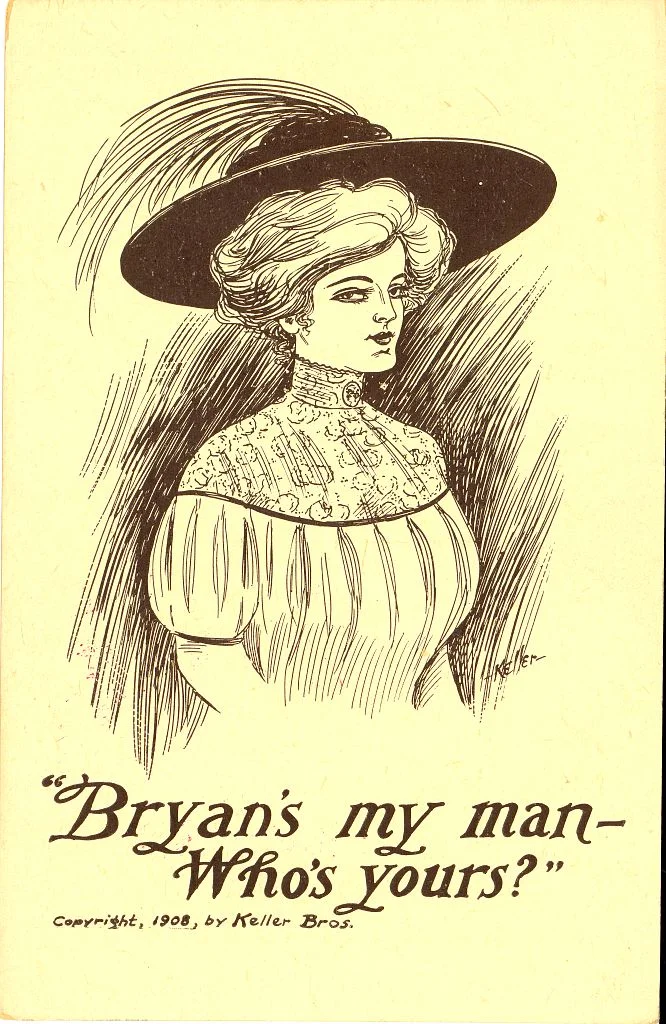

Anonymous. “Bryan’s my Man – Who’s Yours?” Keller Brothers. Zinc Plate Lithograph Postcard. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540