THE ELECTION OF 1896

The Panic of 1893, one of America's most devastating economic collapses, placed the Democrats on the defensive and restored Governor McKinley's stature in national politics. McKinley dominated the political arena at the opening of the 1896 Republican presidential nominating convention held in St. Louis. His commitment to protectionism as a solution to unemployment and his popularity in the Republican Party—as well as the behind-the-scenes political management of his chief political supporter, affluent businessman Marcus Hanna of Ohio—gave McKinley the nomination on the first ballot. He accumulated 661 votes compared to the 84 votes won by his nearest rival, House Speaker Thomas B. Reed of Maine.

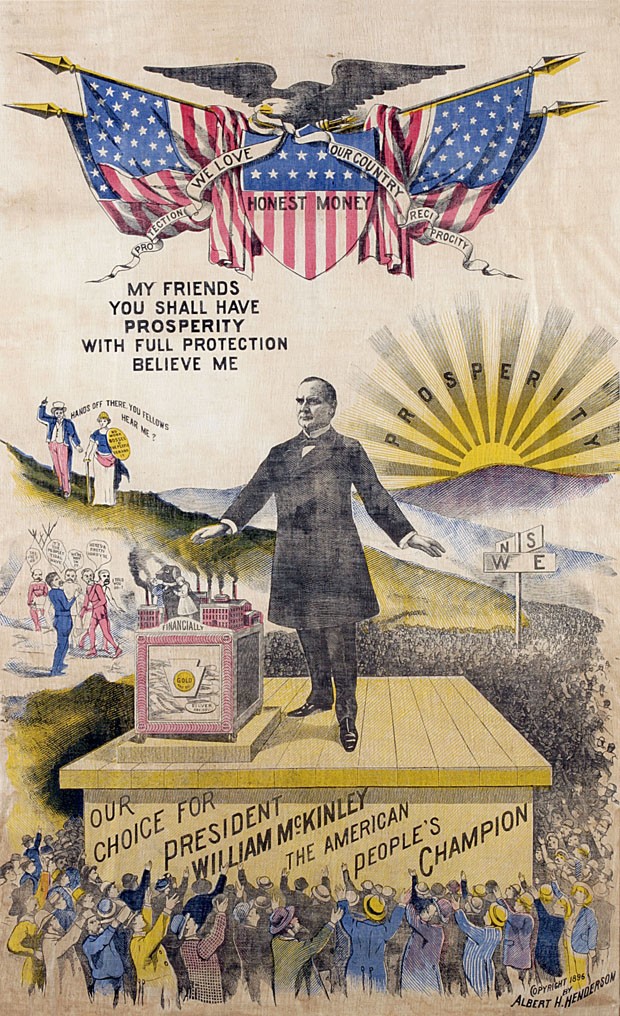

The Republican platform endorsed protective tariffs and the gold standard while leaving open the door to an international agreement on bimetallism. It also supported the acquisition of Hawaii, construction of a canal across Central America, expansion of the Navy, restrictions on the acceptance of illiterate immigrants into the country, equal pay for equal work for women, and a national board of arbitration to settle labor disputes.

The Democrats, meeting in Chicago, rallied behind William Jennings Bryan, a former congressman from Nebraska. A superb orator, Bryan stirred Democrats with his stinging attack on the gold standard and his defense of bimetallism and free silver. He won the nomination on the fifth ballot. The Democrats pegged their hopes for victory on their opposition to (1) the protective tariff, (2) the immigration of foreign "pauper labor," and (3) the use of injunctions to end strikes. They also supported a federal income tax, a stronger Interstate Commerce Commission, statehood for the western states (Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona), and the anti-Spanish revolutionaries in Cuba, who were also supported by the Republicans.

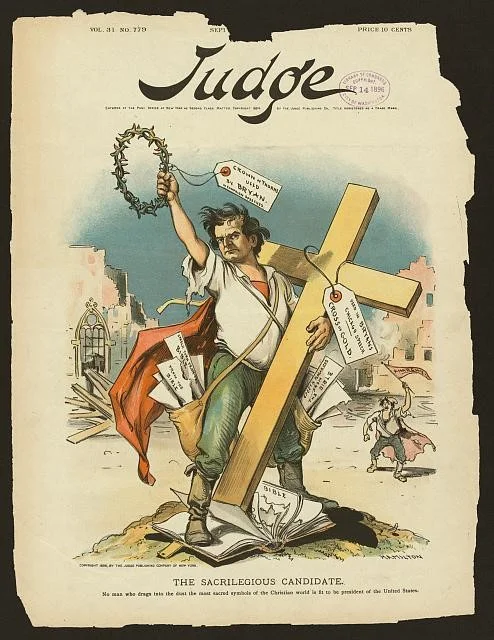

Realizing that the Democrats had stolen their thunder on free silver, the insurgent Populist Party, which sought to organize and support farmers' interests, fused with the Democrats to nominate Bryan for President. Faced with the loss of the Solid South and the Far West, owing to the silver issue, the Republicans raised a staggering $4 million for the campaign. A majority of the contributions came from business, particularly protectionist manufacturers who supported high tariffs and bankers who wanted to maintain sound money policies. Most of these funds went into the printing and distribution of 200 million pamphlets. McKinley, following the tradition of previous candidates who campaigned for President from their homes, delivered 350 carefully crafted speeches from his front porch in Canton to 750,000 visiting delegates. Some 1,400 party speakers stumped the nation, painting Bryan as a radical, a demagogue, and a socialist. Republican speakers de-emphasized their party's stand on bimetallism and instead championed a protective tariff that promised full employment and industrial growth.

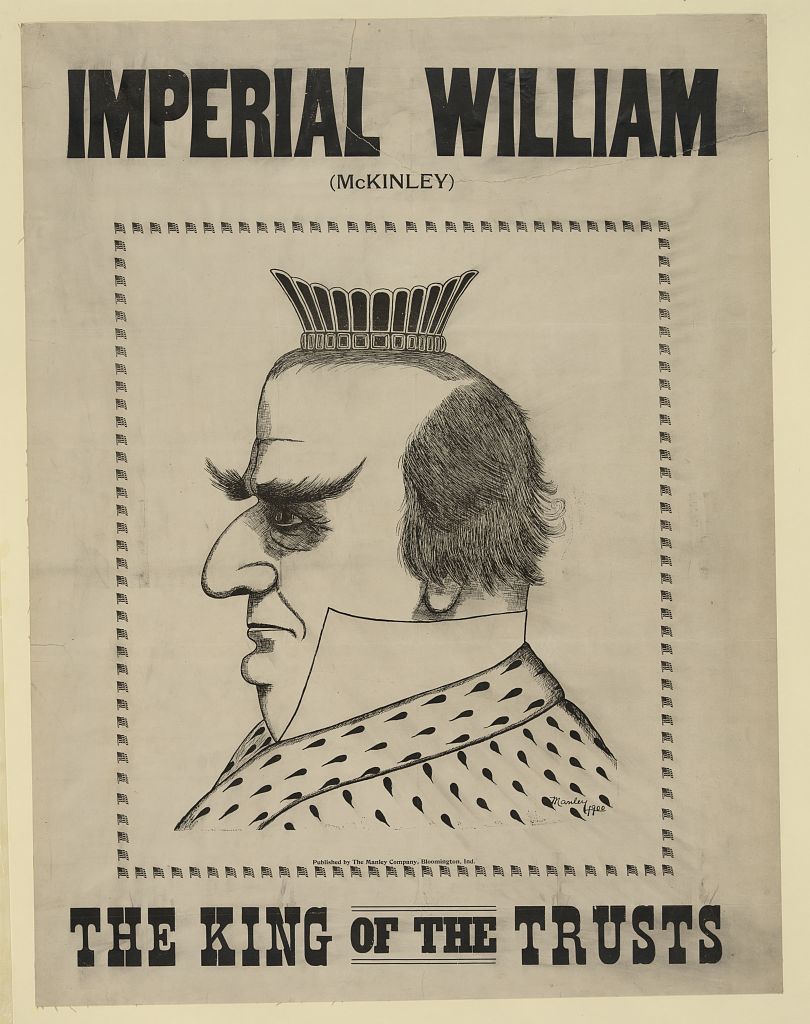

Bryan, in response, stumped the nation in a strenuous campaign, covering 18,000 miles in just three months. He spoke to wildly enthusiastic crowds, condemning McKinley as the puppet of big business and political managers. However, midway through his campaign, Bryan's pace faltered. His strategy for dual party support failed. Gold Democrats bolted the party, unhappy with Bryan's stand on bimetallism and free silver. Some urban-based progressives, who worried about Bryan's evangelistic style and moralistic fervor, also deserted the Democrats. Moreover, Bryan failed to build support outside his Populist and agrarian base, especially in the face of McKinley's effective campaigning on economic issues.

Bryan lost to McKinley by a margin of approximately 600,000 votes, the greatest electoral sweep in twenty-five years. McKinley received over a third more electoral college votes than Bryan. The Republican victory reflected a winning coalition of urban residents in the North, prosperous midwestern farmers, industrial workers, ethnic voters (with the exception of the Irish), and reform-minded professionals. It launched a long period of Republican power lasting until 1932, broken only by Woodrow Wilson's victory in 1912, which occurred principally because of a split in the Republican Party.

Source: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “William McKinley: Campaigns and Elections.” Accessed May 23, 2016. http://millercenter.org/president/biography/mckinley-campaigns-and-elections.

Anonymous. c.1896. "Imperial William (McKinley) the King of the Trusts." Manley Company. Print. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540

Grant E. Hamilton. 1896. "The Sacrilegious Candidate." Judge. Chromolithograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540

Albert H. Henderson. 1896. "William McKinley Campaign Banner." Printed Cotton. From the New York Historical Society, as covered in "25 Amazing Political Artifacts." 2012. in Complex Accessed May 23, 2016. http://www.complex.com/style/2012/11/25-amazing-political-artifacts-from-the-new-york-historical-society/william-mckinley-campaign-banner