THE CAMPAIGN OF 1868

President Abraham Lincoln's assassination at the end of the Civil War was a tragedy beyond measure. It deprived a shattered nation of great leadership when it was most needed. Lincoln's successor, the uncharismatic Andrew Johnson, took charge of an embattled and ineffective administration.

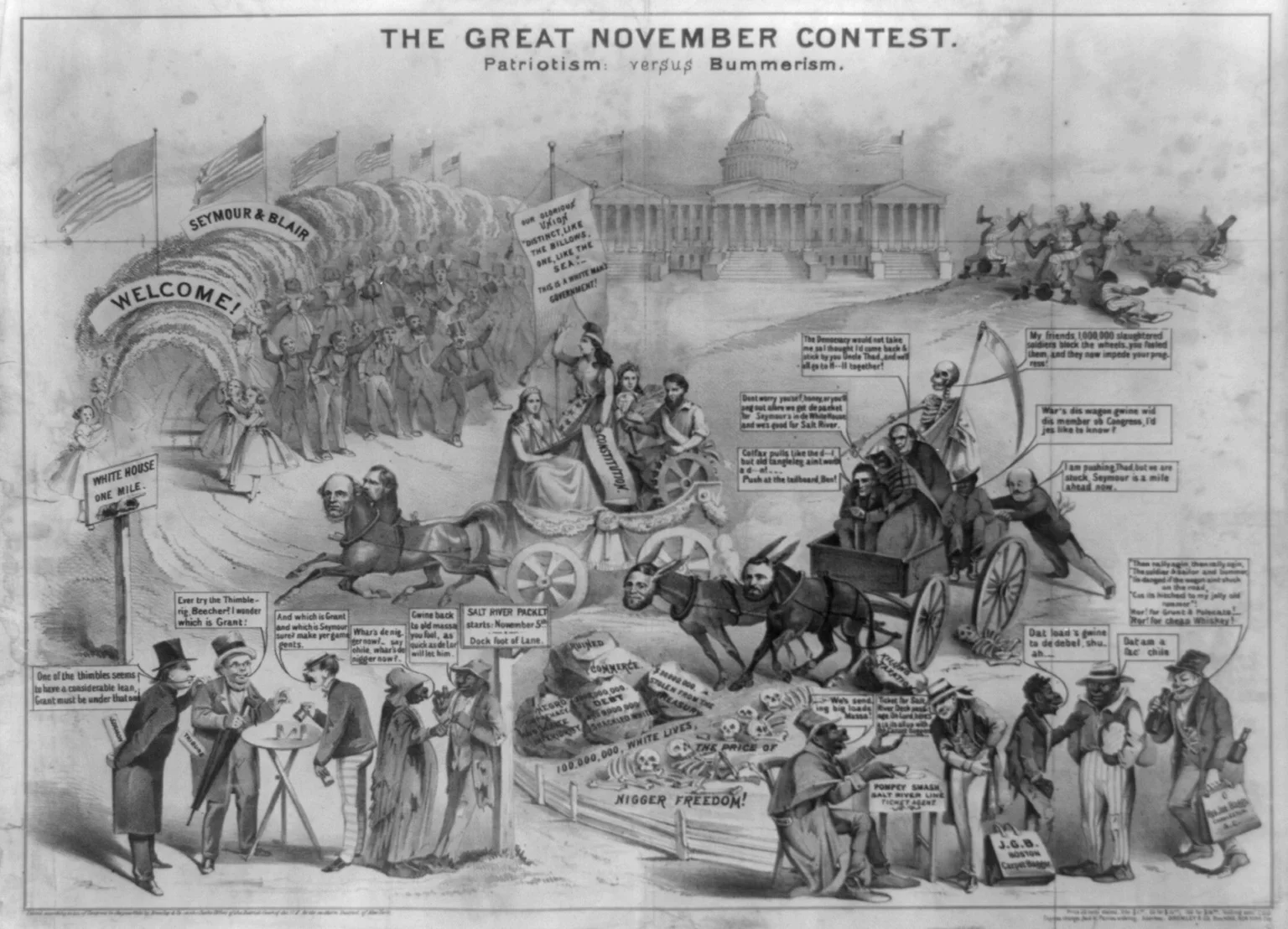

The critical question in the aftermath of the Civil War was what to do with the defeated South. Congress and the President struggled to find a balance between support for black civil rights and support for white leadership. This effort at Reconstruction, at bringing the shattered South back into the Union, nearly destroyed the Johnson administration. Johnson wanted to reunite the nation as rapidly as possible while maintaining the electorate as an exclusively white entity. He had comparatively little interest in protecting the rights of the newly freed slaves. The Republican Party was divided over the President's approach to Reconstruction. The Radical Republicans supported policies that did not allow the leaders of the Confederacy to hold political power and provided African Americans with civil and political rights, including the right to vote. They were opposed in that effort by many moderate Republicans and nearly all Democrats.

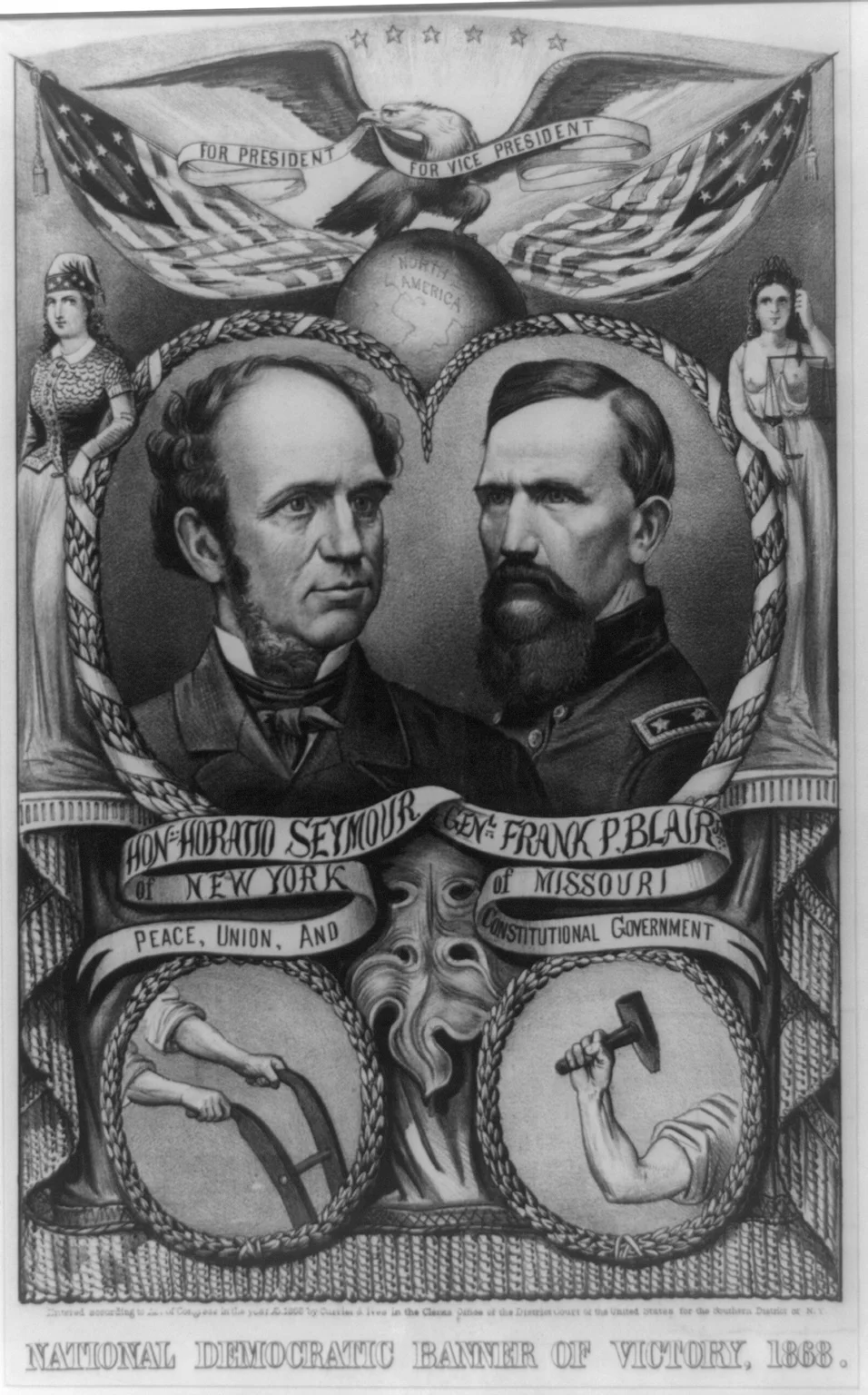

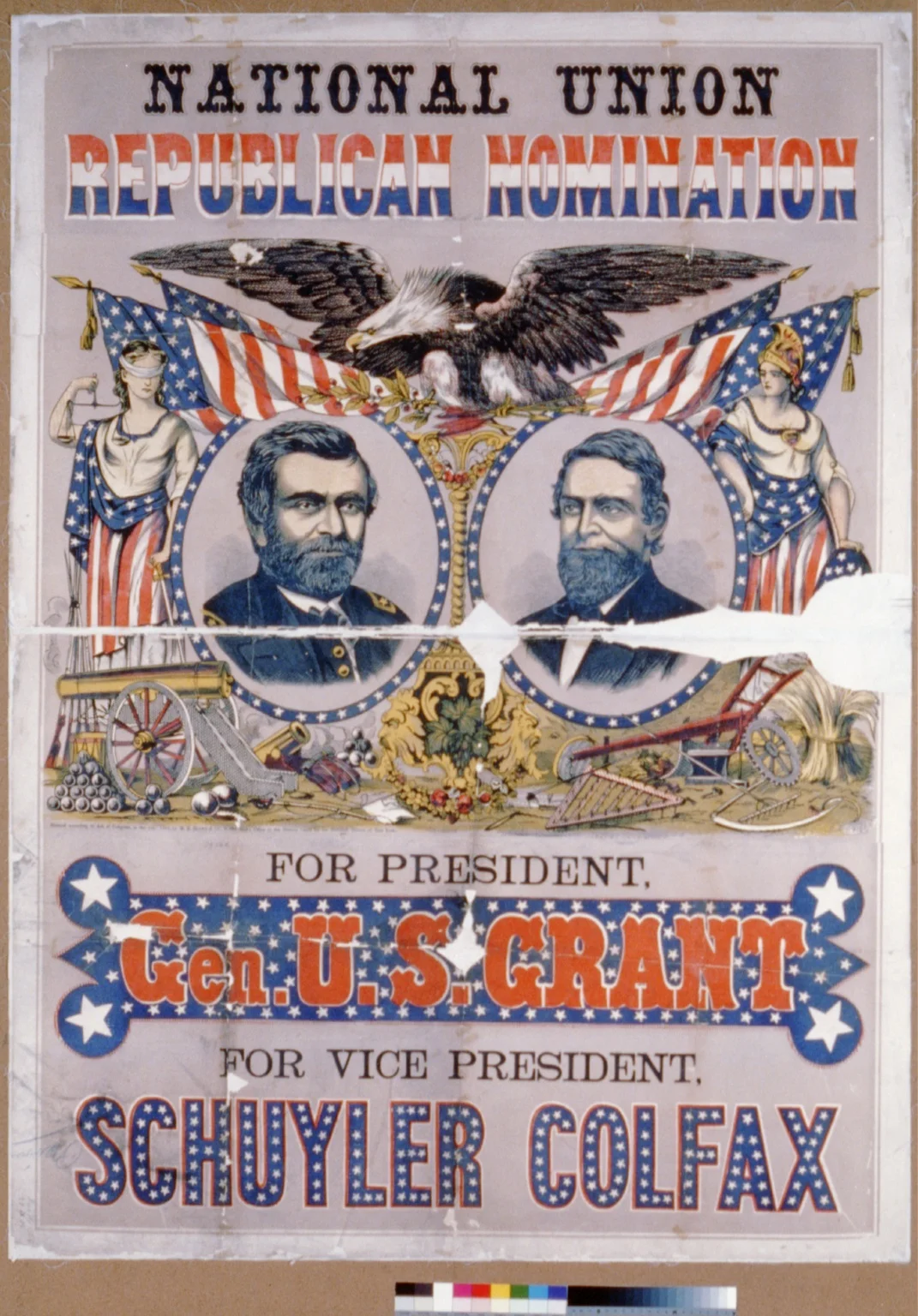

At the beginning of the Reconstruction era, Grant, as general of the armies, attempted to work with Johnson. However, he did not like the President's policies, which he thought repudiated the war's legacy. A dispute arose between the two in 1867 when Grant refused to back Johnson in his struggle with Congress. Thereafter, the general moved increasingly towards the Radical's viewpoint. He came to believe that the federal government had to preserve the sacrifices of the war by protecting African Americans from racist Southern governments and preventing former Confederates from retaking power. The Radicals began to court Grant with the idea of running him for President. Grant claimed that he had little interest in the presidency, but popular demand for his candidacy was too strong. At the Republican Party convention in 1868, Grant's nomination, which he won on the first ballot, was a mere formality. Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax of Indiana was designated his running mate. The Democrats named New York governor Horatio Seymour to oppose them. As was the custom of the times, the 46-year-old Grant did not campaign. But he was easily the most popular candidate, and his election was never seriously challenged. He won the Electoral College vote by a nearly 3:1 margin over Seymour. Helped by the newly enfranchised Southern blacks in some reconstructed states, he won the popular vote by 300,000.

After four years in office, Grant's popularity was still high but a segment of the Republican Party was disenchanted with his policies. They split from the Republican Party to challenge Grant, calling themselves the Liberal Republicans. They opposed the President's policies in the South, specifically his support for civil rights for African Americans and federal government intervention in the South. They wanted to replace Reconstruction in the South with local self-government, which essentially meant the return of white rule. The Liberal Republicans nominated Horace Greeley, founder of the New York Tribune, as their candidate. The Democratic Party, thrilled at the divided Republicans, jumped on the Greeley bandwagon, nominating him as its candidate as well. However, the eccentric newspaper man was no match for Grant. Greeley supported high tariffs (even though the Liberal Republicans advocated free trade) and had switched sides on many major issues—for example, he first supported secession but then later called for total war against the South, he wanted a tough Reconstruction but amnesty for former Confederates. Election results rejected Greeley and the Democratic platform with the electorate confirming Grant's stature by a margin of 56 percent to 44 percent and an Electoral College majority of 286 to 66. The President's reelection victory also brought an overwhelming Republican majority into both house of Congress.

Source: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Ulysses S. Grant: Campaigns and Elections.” Accessed May 23, 2016. http://millercenter.org/president/biography/grant-campaigns-and-elections.

Anonymous. 1868. "National Democratic banner of victory, 1868." Currier & Ives. Lithograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540.

Anonymous. 1868. "National Union Republican Nomination: For President General US Grant. For Vice-President Schuyler Colfax." Clarry & Reilly (firm) and M.B. Brown & Company (firm). Color Woodprint. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540.

Anonymous. 1868. "The great November contest. Patriotism: versus Bummerism." M.B. Brown & Co. Lithograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 .